Maillol et Rodin

Auguste Rodin (1840 – 1917), lors d’un dîner chez Vollard, est interrogé: « Si nous ne vous avions pas Maître, la sculpture, aujourd’hui… » ? Rodin répondit en montrant Maillol : « Et celui-là donc ? »

5 MINUTES

Auguste Rodin (1840 – 1917), during a dinner at Vollard’s, was asked: “If we hadn’t had you Master, what would sculpture be today? Rodin replied, pointing to Maillol: “What about that one?”

5 MINUTES

5 MINUTES

Key players in sculpture at the beginning of the 20th century, Rodin and Maillol had different temperaments. Maillol never bothered to document his work, while one of Rodin’s main aims at the end of his life was to museumize his work. Very early on, art critics focused on their differences: Maillol became the hero of composition, while Rodin expressed emotion in sculpture.

Comparing the works of these two artists was a common phenomenon throughout the twentieth century. In 1947, Henri Matisse asked Maillol’s son Lucien if it would be possible to loan a plaster cast of L’Action enchainée (Action in Chains) so that it could be compared with the plaster cast of Rodin’s Saint-Jean Baptiste (St John the Baptist) [ill. 1].

These similarities and differences are all the more interesting when we consider the personal relationship between the two artists, as documented in Count Kessler’s diary.

“ Acteurs essentiels de la sculpture au début du XXème siècle, Rodin et Maillol possèdent des tempéraments différents. ”

In 1900, Rodin organised his first major retrospective in Paris, at the Place de l’Alma, as part of the Universal Exhibition. This pavilion gave the sculptor, then aged sixty, a dominant position on the European artistic scene. At the time, he maintained a large studio, with a considerable number of students and professionals, including Bourdelle, Despiau, Brancusi and François Pompon. Although Maillol was twenty years younger than Rodin, he was not his master. Indeed, while most of the sculptors of his generation began training with Rodin in 1890, Maillol was devoting himself to painting and the decorative arts at the time. It was not until around 1900 that Maillol began to produce and exhibit sculptures.

This distance between Rodin and Maillol created an opposition between the art of the two artists. The age difference led to Maillol being seen as the symbol of a revival in 1905, with the tranquil grandeur of the Méditerranée, which was contrasted with the tormented agitation of Rodin in the 1880s and 1890s.

The parallels between these two artists are apparent from Maillol’s beginnings in sculpture: Gide writes: “We have just seen, in a special room on the ground floor, unequal works by M. Rodin [….], each panting, restless, meaningful, full of impassioned pathos. We arrive on the first floor, in this not very large room, in the middle of which rests the great seated woman by M. Maillol. It’s beautiful; it means nothing; it’s a silent work”. Thus, very early on, Maillol became the embodiment of a new modern path in sculpture, that of the twentieth century, whereas Rodin appeared to be the champion of the late romanticism of the nineteenth.

In those years, Maillol felt a kind of intimidated admiration for Rodin. “”Art is complicated”, I [Maillol] said to Rodin, who laughed because he felt I was struggling with nature”. This same feeling is summed up later: “Rodin was a god. When I went to see him, I had the impression of being received by a benevolent god”.

It was probably thanks to Maillol’s first solo exhibition, organised by the art dealer Ambroise Vollard in his gallery on rue Laffitte in June 1902, that Rodin became aware of the existence of this new sculptor on the Parisian scene. The art critic Octave Mirbeau bought a bronze copy of the statuette Léda [ill. 2]. which he showed to Rodin and whose opinion he recorded.

Il témoigne d’une attention forte aux mouvements de la peinture moderne : la palette claire, la liberté du ton coloré et la touche fractionnée sont tout à fait dans le goût de la peinture impressionniste.

Aristide Maillol

“The other day, Rodin was here. Like me, he had taken your Léda in his hand. And he turned her over in all directions, in all her profiles, and he looked at her, observed her, scrutinised all of her.

– It’s absolutely beautiful! he said, what an artist!

Then he continued looking

– And do you know why it’s so beautiful, and why you can enjoy looking at it for hours and hours? It’s because it doesn’t arouse curiosity [ill. 3].

Rodin praised Maillol’s ability to create sculpture without artificial effects that would arouse the viewer’s curiosity. He appreciated a sculpture that stood out for its purity and simplicity.

In July 1911, when he saw L’Été inachevé (Unfinished Summer) in the studio at Marly [ill. 4 and 5], he said: “This is beautiful, it’s very beautiful… it’s as beautiful as a Greek statue. It’s absolutely right, absolutely right.” This was a huge compliment from Rodin, for whom the antique was synonymous with perfection. Indeed, for him, “if Greek artists are greater than others, it is because they have come closest to nature”.

Maillol’s beginnings were thus closely linked to Rodin’s view of his art, as confirmed by the first major article devoted to him. Once again, it was Mirabeau who passed his assessment of the artist’s qualities on Rodin’s comments on Léda.

“Maillol is a sculptor as great as the greatest. You see, in this little bronze, there is an example for everyone; for the old masters as well as for the young beginners… I am happy to have seen it… […] Maillol has the genius of sculpture […] What is admirable about Maillol, what is, I might say, eternal, is the purity, the clarity, the limpidity of his craft and his thought.” In his own way, Rodin supported Maillol.

On 2 August 1904, he bought a statuette of his younger son from Vollard for 500 francs and kept it all his life [ill. 6]. Maillol was extremely touched by this purchase, as he considered Rodin to be one of the greatest masters of sculpture. He expressed this by thanking Rodin: “This is the true reward, the only one that the artist in love with his art hopes for from his work – and what’s more, it is an encouragement for me. One walks more surely in one’s path when the great artist at the summit of his glorious career casts a glance at the humble worker who is coming up behind him”.

In 1903, the year he exhibited his first sculpture Femme au bain (Woman in the Bath) at the Salon national des Beaux-arts, Maillol was happy to write to his painter friend Rippl-Rónai that “Rodin speaks very highly of me, I went to see him and had lunch with him”.

“ Les débuts de Maillol sont ainsi étroitement liés au regard de Rodin sur son art ”

Although a relationship gradually developed, Maillol still felt a sense of inequality during these years. He complained about his condition to Kessler in August 1904: “I don’t have a model. Rodin can afford as many models as he likes, but we artists usually have to use our wives”.

From 1907 onwards, Maillol became an established sculptor, receiving numerous commissions from Count Kessler and the State. At the same time, a closer friendship developed with Rodin. On 25 May, he visited Rodin’s studio in the rue de l’Université, and on 14 Auguste, Rodin visited him in Marly [ill. 7].

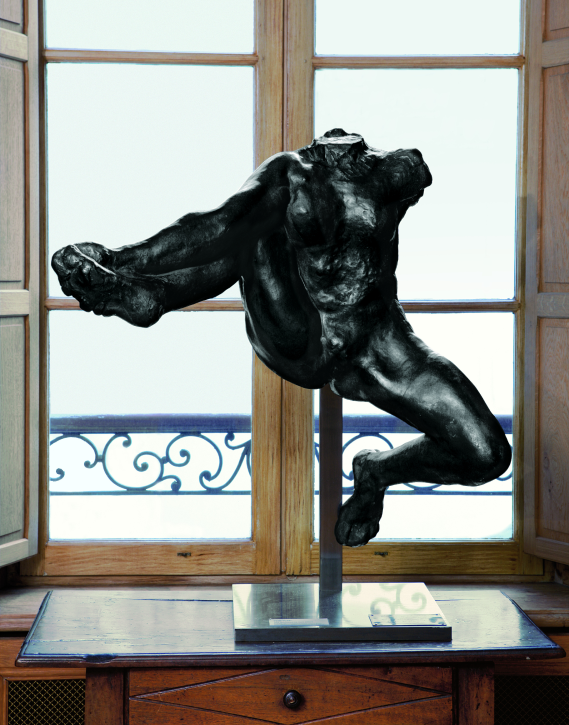

The close relationship between the two artists can also be seen in Maillol’s work, when he created two of the most atypical sculptures in his oeuvre. Since 1905, he had been working on the commission for the “Monument à Blanqui”, which lead to l’Action enchainée (Action in Chains) [ill. 8]. Here, he moved away from his full, calm style in favour of restless movement. The female figure seems to be wiggling in an attempt to free herself from the bonds that restrain her, embodying the struggle and imprisonment experienced by the socialist revolutionary Auguste Blanqui. The sense of agitation and distress in this sculpture makes it a kind of antithesis to Méditerranée. This is one of the rare occasions when Maillol introduces movement into his sculpture. He probably took Rodin’s L’Homme qui marche (The Walking Man) as a reference [ill. 9] and the firm planting of his legs in the ground. The twisting of the torso could also come from La Voix intérieure (The Voice Within) [ill. 10].

A few months later, Kessler commissioned Maillol to create a sculpture of a male nude, Le Cycliste. His model for this work was of a naturalism that was rare in his oeuvre. Rodin, who was very taken by this sculpture, said “I wouldn’t have believed you capable of doing that”, no doubt seeing in it a link with one of his very first sculptures, L’Àge d’Airain.

Maillol criticised Rodin’s lack of attention to the overall effect in favour of the fragment, which was contrary to his approach, which was based on addition. He realised this as early as 1904: “Rodin makes a beautiful piece, a leg, a hand, but he doesn’t care about the whole, the broad lines. […] I’m quite the opposite. [I start] from the great decorative line”.

When Kessler asked Maillol about Rodin’s art, Maillol actually thought that Robin had a painterly quality to his sculpture: “He expresses himself with spots, shadows and light”. In the end, “all we see are reflections; we look for the form, but we don’t find it”. However, Maillol tempered his judgement, saying that Rodin sometimes managed to “create a form”, referring in particular to La Voix intérieure [ill. 10]: “It was she who reconciled me with Rodin”.

Rodin thus emerged as a tutelary figure at the start of Maillol’s career. He was one of the first enthusiasts of his art, although he was aware that he did not belong to the same generation. In a way, Maillol occupied a similar position in sculpture between 1917 and 1944 to that occupied by Rodin between 1890 and 1917: the embodiment of a new impetus in sculpture. This dimension is echoed in a prophetic remark by Rodin, reported by Paul Sentenac: “Maillol, when I die, you will replace me”.

Maillol was attracted to Rodin’s work. In 1905, he had in his home in Marly, “in the place of honour, on the sideboard, a powerful plaster by Rodin”. We also know that he owned a “De Balzac”, a reclining woman, probably the “Torso of Adèle”, and some small-format hands by the master.

In September 1904, on his way to London with Count Kessler, he stopped off in Calais to see the Les Bourgeois monument, which he found remarkable. He said to Kessler: “Obviously it’s for yourself, you have to see it up close, it’s not decorative. But Rodin expressed what he wanted to say very well, the lamentable, disorderly side, the herd”. To Rodin, he wrote: “This is the most beautiful modern work – what emotion […] your admirer, Maillol”.

Maillol’s view of Rodin was singular in that he understood his artistic intentions but had no desire to emulate them. Maillol brought his own intuitions to sculpture, which barely depended on the influence of his older colleague.

In this way, Maillol allowed himself critical freedom with regard to Rodin’s work. Of “Iris Messagère des Dieux” (Iris, Messenger of the Gods) [ill. 11], he commented on the arm, leg and thigh that “these are unheard-of pieces, incredibly well executed. The sex is studied, it’s lifelike… and then he didn’t put the head on, he didn’t finish the torso, he left it like that, he abandoned it… but what a tasteless presentation, on that wire! It’s ridiculous”.

– Octave Mirbeau, « Aristide Maillol », La Revue, 1er avril 1905, p. 321-344. Disponible en ligne : https://gallica.bnf.fr

– Judith Cladel, Maillol, sa vie, son œuvre, ses idées, Paris, Bernard Grasset, 1937.

– Collectif, l’ABCdaire de Maillol, Paris : Flammarion, 1996.

– Dorottya Gulyás, Eszter Földi, Rippl-Rónai-Maillol, The story of a Friendship, catalogue d’exposition, du 16 décembre 2014-26 avril 2015, Budapest, Galerie Nationale hongroise.

– Henri Frère, Conversations de Maillol, Paris, Somogy Edition d’art, 2016.

– Comte Harry Kessler, Journal : Regards sur l’art et les artistes contemporains, 1889–1937, Paris : Éditions de la Maison des sciences de

l’homme, 2017. Disponible en ligne : https://books.openedition.org/editionsmsh/10902?lang=fr

– Claire Muchir, Antoinette Le Normand-Romain, Alex Susanna, Rodin-Maillol face à face, catalogue d’exposition, musée d’Art Hyacinthe Rigaud, Perpignan, du 22 juin au 3 novembre 2019, Silvana Edition, 2019.

– Antoinette Lenormand-Romain, Ophélie Ferlier-Bouat Aristide Maillol 1861- 1944, la quête de l’harmonie, catalogue de l’exposition, Paris, Musée d’Orsay, 12 avril au 21 août 2022, Zürich, Kunthaus, 7 octobre au 22 janvier 2023, Roubaix, La Piscine-Musée d’art et d’industrie André Diligent, 18 février au 21 mai 2023, avec le partenariat exceptionnel de la Fondation Dina Vierny – Musée Maillol, Paris, Gallimard, 2022. Portail des collections du Musée Rodin : https://collections.musee-rodin.fr/

Prenez le meilleur du Musée Maillol en devenant membre

Mentions légales | CGU | Données personnelles | Gestion des cookies

Musée Maillol, 2021

Mentions légales | CGU | Données personnelles | Gestion des cookies

Musée Maillol, 2021